By David P. Diaz, Ed.D.

[Note: The following article served as the first draft of a chapter in the book: The Genesis Labyrinth (2nd ed., 2020).]

The Old Testament is a narrative that is set in history. No matter how you interpret the content, it is difficult to mistake clear references to people, places, dates, times, seasons, and events. In short, it contains everything that one would expect to find in a historical narrative. Although there are other genres included in the Old Testament (i.e., poetry, wisdom, law, prophecy, etc.), even those should be interpreted within the historical context in which they were written. If we agree that the Bible makes specific historical assertions, then the question that naturally presents itself is: Can we know any objective truth about ancient history? This question crosses my mind frequently when I hear people reject historical claims simply because they are found in the Bible and not some other book of ancient history. These types of criticisms are generally always focused on the Judeo-Christian Scriptures, no doubt because they are inseparably tied to miraculous events that purportedly occurred in history: the creation of man, the flood, the parting of the Red Sea, the ten plagues of Egypt, and others. It seems that skeptics are almost always more willing to accept historical claims in ancient secular literature than those found in the Bible, even when the statements have nothing to do with supernatural claims. But is this really necessary? The following brief article will focus on the reliability of the Old Testament.

What is Reliability?

What are we really talking about when we speak of the historical reliability of an ancient document? In short, the claim that the Bible is “reliable” means that it is a trustworthy and highly accurate representation of the original words of the authors. What complicates this matter is that the original writings no longer exist, so our translations are based on the numerous ancient copies of the manuscripts that have been collected from around the world. By comparing the text of these existing manuscripts, biblical scholars can get a good idea of how faithfully the words have been transmitted. This is the job of historical-critical scholarship, which carefully examines the number and type of variants between the ancient documents.

The question then becomes, “How does one verify the statements of fact contained within the Bible?” Unlike other scientific disciplines, history cannot observe and repeatedly test historical events. Within the ebb and flow of history, these bygone incidents have taken place only once, which places them outside our ability to observe and repeat the observations. The discipline of history studies singularities of the past—not repeatable events of the present. Therefore, historical research relies on the witness of ancient documents and artifacts, typically dug up by archaeologists. The historian must reconstruct the past from fragmentary historical finds. Such is the science of ancient history and archaeology.

We have learned much about ancient history through such classic writings as Homer’s Iliad, Caesar’s Gallic Wars, the Annals of Tacitus, as well as the Bible. But it would be a mistake to think that archaeology can prove every historical claim found in ancient documents. As Edwin Yamauchi (1972, 18, 20) has noted:

[A] popular notion exists that “archaeology has proved the Bible.” There is truth to this aphorism… but it needs to be understood properly. If by “proof” is meant irrefutable evidence that everything in the Bible happened “just so,” this “proof” cannot be provided by archaeology.

Josh McDowell (1999, 92) has provided a similar warning with respect to theological truths found in the Bible:

Archaeology cannot “prove” the Bible, if by this you mean “proves it to be inspired and revealed by God.” But if by “prove” one means “shows some biblical event or passage to be historical,” then archaeology does prove the Bible.

By way of illustration, let’s say we found two ancient clay tablets somewhere in the Near East with the Ten Commandments inscribed on their face. We could confirm whether or not the inscriptions were in the correct language and dialect of the time and whether or not the inscriptions were made using the correct instrument and with the proper technique. We could date them to see if they were in the appropriate period of history, and we could assess whether the location where they were found places them in the expected region of the genuine article. With this information, we could then build a case that these were indeed the original tablets (or not). But, even if the tablets could be demonstrated to a high degree of probability to be “the real McCoy,” we would not be able to prove that God gave them to Moses. In other words, the Bible contains many theological truth-claims, as well as certain historical claims, that are insusceptible to archaeological or historical proof.

Thus, what we mean by historical proof or reliability, typically involves providing evidence that an event described in an ancient document actually occurred—or that a place, person, or thing mentioned in the text actually existed—within the proper time frame and location in which it was purported to have existed or taken place. The more evidence that can be produced, the higher the probability that an event actually happened or that a place or person actually existed. In this sense, history is looking for plausible and probable explanations for the evidence that it finds, not necessarily ironclad proof about all things mentioned in the text.

Markers of Historical Reliability of the Old Testament

How does one decide if the text of the Old Testament is historically reliable? According to McDowell (1999, 69), the Old Testament has been shown to be reliable in three different ways. First, the textual transmission (i.e., the process used for copying the manuscripts) has been demonstrated to be highly accurate, a fact attested by comparisons of the hundreds of manuscripts and fragments discovered throughout history. Second, many of the purported facts in the Old Testament have been supported and/or confirmed by archaeological evidence (e.g., artifacts from ancient societies that testify of biblical events). Third, through textual studies, the documentary evidence (i.e., comparison with non-biblical texts and other written artifacts) has demonstrated the Old Testament to be reliable.

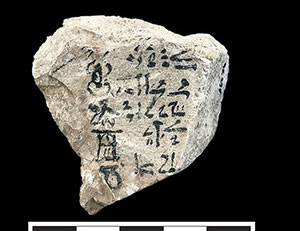

For example, Kitchen (2006, 3) has noted that in Syria, the Mari archives (c. 1700 BC) have yielded 20,000 tablets, which show that the Mare-Yamina (people) existed in wandering settlements that covered all but the extremities of the journeys of Terah and Abraham from Ur to Canaan (Ibid, 316). These facts independently authenticate the places of sojourn of these biblical patriarchs as recorded in the Old Testament. The Mari letters (as well as another ancient Akkadian tablet [c. 1554 BC]) also confirm that patriarchal names such as Abraham, Jacob, and Benjamin were most likely in common use during the same biblical time frames (Archer 2007, 142–143). As Randall Price (2017, 73–74) pointed out: “Since names tend to be unique to a given time period, this evidence helps confirm the chronology of the patriarchs.”

The Ebla tablets, spanning the 24th through the 17th century BC, show that the people, places, and events referred to in the Old Testament narrative correspond, with remarkable accuracy, to that period’s geography and culture (Hanna 2011). Holden and Geisler (2013) explained that for many years critical scholars claimed that Genesis couldn’t have been written prior to 700 BC because the words used were developed long after the stories of Genesis. However, the content of the Ebla tablets has changed the direction of this discussion. They noted:

…the patriarchal narratives found in Genesis accurately utilized or reflected many of the words, names, customs, and locations found in the earlier Ebla tablets. This eliminates the notion of late word origination and supports Genesis as accurately reflecting the ancient world prior to 700 BC. In addition, personal names, locations, and deities found in the tablets are also mentioned in Genesis and the Old Testament (p. 86).

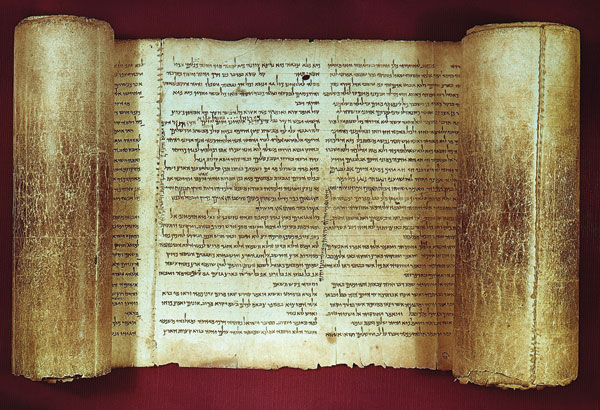

Another discovery, the Dead Sea Scrolls, has demonstrated the reliability of the Old Testament in spectacular fashion. Unearthed in 1947 on the west side of the Dead Sea, this discovery ultimately revealed over two hundred manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible, including an ancient and complete scroll of the Old Testament book of Isaiah (1QIsaa, “Isaiah A”). Prior to this time, the oldest complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible was from the tenth century AD, but the Isaiah A scroll was dated 125 BC, over a thousand years earlier. By comparing 1QIsaa and a second, Isaiah B, scroll (1QIsab) to the more recent manuscript of Isaiah, scholars have confirmed the unusual accuracy with which the Jewish people preserved their sacred documents. According to Archer (as cited in McDowell 1999, 79), when compared with the book of Isaiah in the standard Hebrew Bible, the Isaiah B scroll proved to be word-for-word identical in more than 95 percent of the text. The 5 percent deviation was a result of obvious slips of the pen and variations in spelling. Yale archaeologist Millar Burrows (1986, 304) summarized the relevance of this finding: “It is a matter of wonder that through something like a thousand years, the text underwent so little alteration.” These discoveries and hundreds more have confirmed many of the historical claims made in the Old Testament and have established the general reliability of the transmission of the biblical text.

Whether scholars are questioning the historical authenticity of the Egyptian Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor, the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, the Egyptian Book of the Dead, the Sumerian Lament for Ur, the Vedic Sanskrit Yajurveda, or the Greek historical works of Herodotus and Thucydides, the same rigorous standards for determining historicity (i.e., historical reality) are applied to all of the documents, including the Old Testament. When employing this rule of thumb, scholars have found that, of all the works of antiquity, the Bible rises to the very highest levels of the proverbial heap.

Reformed Jewish scholar Nelson Glueck (as cited in McDowell 1999) has flatly stated, “It is worth emphasizing that in all this work no archaeological discovery has ever controverted a single, properly understood biblical statement.” Leading authority on the Dead Sea Scrolls, Millar Burrows (1940, 17), concurred:

The Bible is supported by archaeological evidence again and again. On the whole, there can be no question that the results of excavation have increased the respect of scholars for the Bible as a collection of historical documents . . . in addition to this general authentication, however, we find the record verified repeatedly at specific points. Names of places and persons turn up at the right places and in the right periods.

Bible historian Edwin Yamauchi in his book, The Stones and the Scriptures (1972), sums up his findings this way: “[Christians] will be encouraged to know that the biblical traditions are not a patchwork of legends but are reliable records of men and women who have responded to the revelation of God in history” (165).

William F. Albright, archaeologist, scholar, and professor of Semitic languages, has authored over one thousand publications on archaeology, oriental studies, and the Bible. He summed up the record succinctly, “There can be no doubt that archaeology has confirmed the substantial historicity of Old Testament tradition” (Albright 1942, 176).

Now, lest we become too smug about the historicity of the entirety of the Old Testament, a final word of caution seems prudent. Even with the great successes in confirming the reliability of the Old Testament, there are numerous facts that haven’t been substantiated and even glaring problems that have not been successfully addressed. Further, since the first eleven chapters of Genesis represent pre- as well as primeval history (i.e., the earliest stages in history), it will be more difficult, if not impossible, to determine the reliability of all the events in the earliest chapters of Genesis. Besides the fact that we may never unearth archaeological relics that far back in history, many of the events were simply not witnessed, such as the creation of the sun, moon, and stars. In short, there is still much work to be done, but what has been accomplished is mostly positive.

The takeaway from this article is this: There is no other work of ancient history of comparable age that can match the historical reliability of the Old Testament. However, there are many things in the text for which we have no direct witness (e.g., the creation of the universe). And there are other types of claims that cannot be verified through historiography or archaeology (e.g., miracles, theological truths). Nevertheless, in light of the demonstrated historical reliability of many facts in the Old Testament record, the serious student of the Bible should at very least give the benefit of the doubt to the written record until evidence demonstrates such a notion to be unwarranted.

About the Author

David P. Diaz, Ed.D., is an independent researcher, retired college professor, and publisher of Things I Believe Project. His writings have ranged from peer-reviewed technical articles to his memoir, which won the 2006 American Book Award. Dr. Diaz holds a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Science from California Polytechnic State University, a Master’s of Arts in Philosophical Apologetics from Houston Christian University, and a Doctor of Education specializing in Computing and Information Technology from Nova Southeastern University.

Bibliography

Albright, William F. Archaeology and the Religion of Israel. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins Press, 1942.

Archer, Gleason Leonard. A Survey of Old Testament Introduction. Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 2007.

Burrows, M. The Dead Sea Scrolls. New York, NY: Gramercy Publishing Company, 1986.

Hanna, Mark M. Biblical Christianity: Truth or Delusion? N.p.: Xulon Press, 2011. Kindle edition.

Holden, Joseph M. and N. L. Geisler, The Popular Handbook of Archaeology and the Bible. Eugene, OR: Harvest House Publishers, 2013.

Kitchen, K. A. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2006.

McDowell, J. The New Evidence That Demands a Verdict. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1999.

Price, R. Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology: A Book by Book Guide to Archaeological Discoveries Related to the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2017.

Yamauchi, E. M. The Stones and the Scriptures. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott & Holman Book, 1972.

Good article. Easy to follow and logical. I also appreciated the appendix. Thank you

What do you say to the OT scholars who deny a “Davidic Kingdom?”

This is an excellent and important question, especially since David is mentioned over 1,000 times in the Old Testament and given that David represents a key figure in the genealogical line of Christ.

Since the mid-1990’s, there have been a number of archaeological finds that support the Davidic Kingdom. (1) Tell es-Safi produced evidence of the existence of the city of Gath (Goliath’s hometown) and supported that this was indeed a Philistine city. (2) Evidence from Khirbet Qeiyafa supports that there was an Israelite city (c. 1025–975 BC) whose existence would have required cooperation with an organized city-state network (i.e, the Davidic Kingdom). (3) The Tell Dan Stele and the (4) Mesha Stele both show evidence of the “House of David.” These references, which were inscriptions written by enemies of Israel, clearly showed that surrounding nations viewed the Israelite kings collectively as being of the “House of David.” [Note; The term “House of David” is used nearly two dozen times in the Hebrew scriptures.] (5) There is clear evidence that David moved the Israelite capital from Hebron to Jerusalem. Of course, this location is now well-known as the “city of David.” Quite a few archaeological finds in this city are associated with the “house of David” including numerous bullae (stamp-seal impressions), Hezekiah’s water tunnel, Gihon Spring, retaining walls to David’s Palace (i.e., “Stepped-Stone Structure”) and many others. I think it is safe to say that David is clearly considered to be a historical king who ruled over a unified kingdom of Israel that covered a vast territory.